Chua Jun Yan

This article is part of the RI at 200: History Series.

Mr Yong Nyuk Lin (Minister for Education) speaking at Raffles Institution’s Founder’s Day, 1960

As decolonisation and nationalism gathered pace in the years after World War II, ambiguity shrouded the status of Raffles Institution. At Founder’s Day in 1960, Yong Nyuk Lin – the Minister for Education in the newly-elected People’s Action Party cabinet – recast RI’s history as one of colonial neglect and exploitation. “How far the trustees [of RI] and later the colonial government failed in their responsibility and obligations is the sad history not only of education in this school,” he chided, “but also in Singapore.” For Yong, the sole purpose of colonial education had been to churn out clerks for commercial firms and government departments, so that “those in power could long enjoy their privileges” and “merchant princes [could] rake in their profits.” In a sign of the times, the 1960 Founder’s Day was postponed (ostensibly for the first time in the school’s 137-year history)because the school grounds had been “requisitioned” for the National Day celebration.1

For a period, even the name of the school was cast in doubt. In December 1960, the Legislative Assembly passed ordinances to rename the Raffles Museum and Raffles Library, both institutions with close historical links to RI. Arguing for the changes, Minister for Culture S. Rajaratnam opined that these institutions should serve as symbols “of national loyalty and aspiration.”2 As the editors of the Rafflesian Times (Vol IV No. II, 1964) lamented, Stamford Raffles’ name was “in danger of being lost in our rush to achieve new heights and new horizons.” Only after Singapore’s independence, in 1966, did Deputy Prime Minister Toh Chin Chye assure students that “you need not fear that the name of Raffles Institution will ever be changed.” The very necessity of this assurance reflected the shrugging uncertainty around RI’s role in a decolonising world.

“The Last Rafflesian” written by Goh Ewe Hock

The Rafflesian (Vol 34 No 1, 1960)

Two articles from The Rafflesian (Vol 34 No. 1, 1960), published the year of Yong’s Founder’s Day speech, powerfully expressed the anxieties of RI’s students, who were caught between the colonial and post-colonial worlds. The first was an apocalyptic short story, set in a future when the entire population of Singapore had been wiped out by radioactive clouds. Artificially incubated in a science lab in RI before the cataclysm (but born shortly afterward), the narrator walks around the abandoned school buildings, reflecting on the traces of students and teachers past. The dystopian story critiqued the high modernist project of nation-building, which sought to restructure society along the lines of scientific rationality. As the narrator encounters banners awarded for “National Participation in Loyalty Examinations,” he is reminded that this is where he received his “Senior Certificate which certified to all the world that [he] was a class A guinea-pig.” The title of the piece, “The Last Rafflesian,” questioned the tenability of a traditional colonial institution in this brave new world.

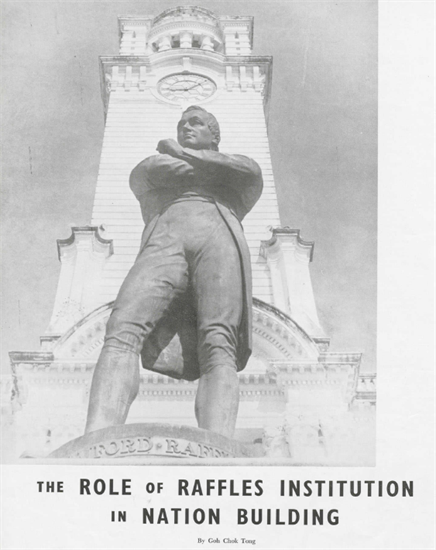

“The Role of Raffles Institution in Nation Building” written by Goh Chok Tong

The Rafflesian (Vol 34 No 1, 1960)

By contrast, the second article sought to articulate the “Role of Raffles Institution in Nation Building,” arguing for an overhaul of the colonial education system to “train our youths to regard Singapore as their home,” rather than to “think in terms of England as the guardian of our rights.” This was to be accomplished through scientific education, to support industrialization; extra-mural activities, particularly uniformed groups, to dispel “communal differences and racial differences,” and above all, the teaching of Malay, the national language, to forge a national identity. Yet the author also defended the figure of Stamford Raffles, pointing out, for instance, that he had proposed the teaching of “native languages” in his plan for the original Singapore Institution. In this formulation, a post-colonial RI was not so much a departure from colonial heritage, but the logical culmination of colonial tutelage. The author of the article was none other than a young Goh Chok Tong.

Read together and in conjunction with Yong’s speech, these pieces offered competing visions for RI’s place in a decolonising world. In one account, RI as it stood was fatally doomed; its continued existence demanded a break from its colonial provenance. In another account, RI’s identity was malleable; its history could be re-appropriated and refashioned to cast the school as a national – rather than colonial – symbol. As educational institutions around the world reckon with their colonial legacies, so too will RI, in the years leading to its Bicentennial. As we engage in conversations about the past, we would do well to listen to voices of the past.

Jun Yan graduated from Yale University in 2018. Outside of work, he enjoys researching local and community histories. One of his ambitions is to visit all of Singapore’s offshore islands.

___

1 “RI Postpones Founder’s Day...First Time in 137 Years,” The Singapore Free Press, 9 June 1960, 3.

2 “Raffles’ Name Will Live On: Rajaratnam,” The Straits Times, 1 December 1960, 7.