By Matthew Ethan Ramli (21S03F) and Thet Hninn Zin (21A13A) Cover image by Neo Xin Yuan (21A01D)

Behind the grand piano at the Yusof Ishak Block atrium lies a room that not many know about. Commonly thought of as just another storage facility, it bears the remains of the previous Heritage Gallery, the long-standing precursor to what we now know as the Raffles Archives and Museum. It has largely remained out of use for the better part of the decade, until a new exhibition discussing the life of Stamford Raffles necessitated its use as an annex of the museum.

To those who have previously peered into the dark, cobweb-strewn space, its refurbishment is astonishing, with its polished wooden flooring and carefully positioned art gallery lighting. This new look befits the novel student-led exhibition about our founder himself, curated against the backdrop of the bicentennial.

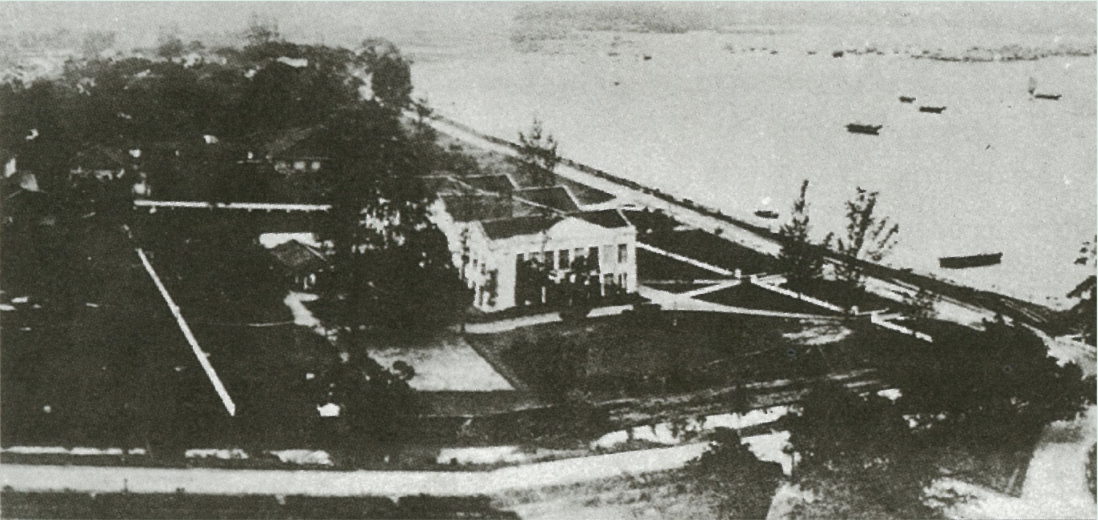

An aerial view of the Singapore Institution, circa. 1860s.

An aerial view of the Singapore Institution, circa. 1860s.

Who was Raffles?

As the title of the showcase, these three words invite all of us to question our beliefs regarding his life and legacy. We start off by considering his role as a statesman, the position we most commonly associate him with.

Beginning from his early days as a humble clerk at the British East India Company, a private enterprise representing the crown, the exhibition chronicles his cumulative rise in rank to the Lieutenant Governor of Java, arguably the most important post in his political career. We are taken through many aspects of his role in Singapore, from his takeover of the island comprising controversial dealings with Sultans and bloody massacres, to policies he championed for rapid modernisation and growth.

When the Dutch retook control of Java after the end of the Napoleonic Wars, Raffles relocated to Bencoolen, on the southeast tip of Sumatra, where he served as an administrator for another five years. The economic failings of the port against the backdrop of the Anglo-Dutch rivalry then created the impetus to find a more centrally-located port, one that we now know as Singapore.

Map of Southeast Asia in the 1800s

Map of Southeast Asia in the 1800s The rest of the Raffles story is something we should all be familiar with: the signing of the treaty with the Johor Sultanate, the creation of the free port, the mapping of the ethnically diverse town plans, and finally, the founding of the Singapore Institution, as it was then called. Surely the exhibition doesn’t feature anything that we don’t already know?

Hold on, the exhibition warns cryptically, arguing for a more holistic view of the narrative. What exactly were Raffles’ contributions in “founding” Singapore? While the nation commemorated the 200th anniversary of the Treaty of Friendship and Alliance last year, attributing much of Singapore’s rapid development to early colonial successes, the exhibition seeks to explore said colonial successes further by uncovering the unsung contributions of those sharing his enterprise and the major falling-outs between them that led to their erasure from the history books.

As many museums across the country stage new exhibitions attempting to revise conventional narratives, we need to ask ourselves why we put Raffles on such a pedestal. After all, his time spent in Singapore totalled less than 9 months, a short duration compared to the first appointed Residents of Singapore, William Farquhar and John Crawfurd, both of whom served integral roles in developing the city.

The unveiling of Raffles’ statue at the Esplanade during Queen Victoria’s Jubilee in 1867. The statue is currently located outside Victoria Concert Hall.

The unveiling of Raffles’ statue at the Esplanade during Queen Victoria’s Jubilee in 1867. The statue is currently located outside Victoria Concert Hall. We base so much of our nation’s identity on Raffles, his name written on history textbooks as the founding father of modern Singapore. As a school for which he laid the foundations, we, too, carry many of his family traditions, adopting his family crest and motto as our own. Having his values as the bedrock of our identities calls into question the values themselves. Was he really the beacon of progress that we perceive him to be?

Yes, the exhibition answers, although we must understand that he was nonetheless a man of his time. As a keen naturist, he commissioned many drawings and research on the nature of the Malayan Archipelago, which was much unknown to the Western world. He also chronicled rich Javanese traditions for ethnography’s own sake, and most importantly, believed in educating the future inhabitants of the island.

One aspect of his liberal pursuit which is much explored in the exhibit was his abolition of slavery in Java, thinking it a colonial responsibility to “uphold the weak, put down lawless force, [and] lighten the chain of the slave”. As modern as his ideas were, they were often slighted by colonial imperatives. In 1812, the aim of extracting natural metals at Banjarmasin, on the south coast of Borneo, led to his relocation of 3200 locals to work as forced labourers.

In the same vein, his colonial perceptions of slavery, i.e. the African slave trade in England itself, led him to ignore the intricate socioeconomic role that slavery played in local communities. Due to the inexistence of the cash economy and credit institutions, people in debt often agreed to work for another person without wages until a specified date, after which they would be free. This was the version of slavery practiced in Java. After the eruption of Mount Tambora in 1815, the locals who had lost their means of subsistence were unable to rely on the safety net of slavery, resulting in a staggering 100,000 deaths.

As for a topic closer to home, Raffles strongly believed in creating an institution that would impart knowledge to the rest of the Malay world and transfer the moral benefits of education from the upper to lower classes. However, despite his efforts to democratise education through the Singapore Institution, as it was then called, this failed to materialise in the early years, when the school mostly served children of wealthy local elites.

A 17th-century portrait of Mount Tambora, which erupted to devastating effect in April 1815.

A 17th-century portrait of Mount Tambora, which erupted to devastating effect in April 1815.In contrast to our traditional understanding of a colonialist, Raffles did not conduct much of the day-to-day administration of the territories that he overlooked. Rather, he sought to gather as much knowledge as possible about the new frontiers. He commissioned the drawing of thousands of previously undiscovered plants and animals across his voyages. However, only 3000 made it safely back to England, the others lost in shipwrecks. He encouraged the proposal of the extant Singapore Botanical and Experimental Garden to the East India Company. Desiring to share his interest in his newfound discoveries with the British community, he finally founded the London Zoological Society in 1826.

Four drawings of birds native to Sumatra from Raffles’ collection. Clockwise: green magpie, blue-backed parrot, crested fireback, and black-naped oriole

Four drawings of birds native to Sumatra from Raffles’ collection. Clockwise: green magpie, blue-backed parrot, crested fireback, and black-naped orioleDespite this, some of his other interests in historiography evidence his role as a colonialist possessing the ideals of his age. His book, the History of Java, was a comprehensive account on local traditions published in 1817. Unlike preceding work about Java by earlier colonialists, which were often political, there was a new focus in noting the rituals and customs of the region. That being said, the work was deeply cluttered with inaccuracies aimed to convince the locals, the Europeans and his own superiors of the contribution of British rule to the prosperity of the island. Paintings show neatly trimmed greenery against unearthed palaces and flourishing agriculture as a result of his land tenure policies.

However, what stands out, interestingly, is how he tried to depict the local civilisation as a “civilised” one as opposed to traditional colonists who portray indigenous populations as primitive to justify colonial exploitation. In an effort to show that the Javanese had “historical consciousness”, a term commonly popularised in Britain as an integral characteristic of a “cultured” civilisation, he described the largely mythical wayang kulit shadow puppet plays as a way of transmission of historical information across generations, although it mostly had the purpose of entertainment. Similarly, drawings of the locals show them with European features and European dancing postures, in contrast to the colonial exaggerations of local caricatures that were more common at the time.

Two drawings of Javanese people that Raffles commissioned for The History of Java: “A Ronggeng or Dancing Girl” (left) and “A Javan of the lower class” (right)

Two drawings of Javanese people that Raffles commissioned for The History of Java: “A Ronggeng or Dancing Girl” (left) and “A Javan of the lower class” (right)In a sense, this exhibition tries to give us a more personal view of Raffles in discussing his interests and beliefs as well as his childhood and family, instead of narrowing in on his “founding” of Singapore.

When asked about the extent of his research for the exhibition, curator Justinian Guan (21S03F) mentioned the sourcing of piles of primary and secondary sources of books not only on Raffles’ life, but also on the zeitgeist, or the spirit of the time in which Raffles lived. The research mainly comprised inquiring upon the vast catalogue of archives at the Raffles Archives and Museum, most of which have not been reviewed before. The compiled research was then sent to an ex-Rafflesian graphic designer to be condensed into panels, before sourcing for traditional crafts from the Malay world that Raffles was likely to find himself engaging with.

Starting in November 2018, the process from start to finish took a whole year. By the end of last year, it was ready for a soft-opening for visitors from the Ministry of Education. Although it added to the workload of preparing for the Year 4 Final Examinations, Justinian described the process as rewarding, the most enjoyable parts being the refurbishment of the room and seeing months of hard work eventually amounting to something greater. He credits Mrs Cheryl Yap, the teacher-in-charge of RAM, his teacher mentors Mrs Sharon Tan and Ms Adriana Wong from the Y1-4 History department, as well as his peers for the successful completion of the work.

Scheduled to open in March this year, the RAM’s opening has been delayed by COVID-19 until the situation improves and students are allowed to gather in groups again. Early estimates would be the end of this year. Yet even with the delayed opening of the exhibition, we can all find out more about what the name “Raffles” means to us, as an institution. With less than a thousand days to our bicentennial, this reconceptualising of our school’s identity in relation to her founder is a task left to all Rafflesians. Justinian hopes that we can actively reconsider our beliefs on who Raffles was holistically, and agree on a fair view of history.

Group picture of exhibition guides and school leaders at the opening, Justinian Guan (21S03F) is in the second row, fourth from left.

Group picture of exhibition guides and school leaders at the opening, Justinian Guan (21S03F) is in the second row, fourth from left.

To find out more about the Raffles Archives and Museum, check out this article: Prelude To Our Bicentennial: The Raffles Archives and Museum

---

For more stories, visit Raffles Press