by Michelle Zhu (15A01B)

Editor’s note: This article was initially published on 24 March 2015 on Raffles Press’ blog, Word of Mouth, a day after the death of the founding Prime Minister of Singapore, Mr Lee Kuan Yew. What follows is a revisiting of the original article.

It is with considerable sadness that we received the news of Mr Lee Kuan Yew’s death. Mr Lee, one of the greatest statesman of our time and the founding father of modern Singapore, was also a Raffles old boy, a school debater and a member of the 01 Scout troop.

Mr Lee (front row, 4th from right) was in the 38th Scouts Troop with Ernie Sheares as his troop leader

The news of Mr Lee’s death brought with it a tidal wave of obituaries. Many lauded him as one of the greatest statesman of our time, while others criticised his more authoritarian ways. However each of us chooses to view Mr Lee’s legacy, none can deny his contributions to making Singapore the country it is today. Yes, we were already a bustling port back in 1965, but we were also struck by a variety of social problems – unemployment was high, much of the population lived below the poverty line, and GDP per capita was just $500, a far cry from the $55,000 that exceeds even that of our former colonial masters today.

There have been numerous articles reminding us of Mr Lee’s achievements, but few of how he came to become the founding Prime Minister we venerate today. An initially reluctant statesman who devoted his adult life to building a nation, Mr Lee Kuan Yew first went to Telok Kurau Primary School and was later a student at the old RI at Stamford Road from 1936—1940, before going on to NUS (then Raffles College) and later LSE and Cambridge.

We know that Mr Lee eventually emerged top of his class in Malaya and the Straits Settlements, earning the prestigious Queen’s scholarship (of which only two were awarded annually), but he initially had a much lower profile in school than we might have originally thought. The Raffles Archives and Museum has kindly opened their archives to Raffles Press, but unexpectedly, the only mentions of Mr Lee we could find in our institution publication, The Rafflesian, were two relatively short mentions of him being involved in debate. In addition, the young Harry Lee was a scout in the 01 Raffles Scout Troop, and also played cricket, tennis and chess, but never became a prefect because of his ‘mischievous, playful streak’, as he later wrote in his memoirs.

Mr Lee was the guest-of-honour for RI’s 146th Founder’s Day in 1969

RI was also where Mr Lee Kuan Yew met his wife and lifelong companion, the late Mdm Kwa Geok Choo. She was the only girl in RI, then an all-boys school, and they developed a friendship that later blossomed into something much more. The age-old adage that ‘behind every successful man is a woman’ could not be more true in his case – his wife played the supporting role in his nation-building endeavours, and was even instrumental in drafting our constitution. In his school days, Mr Lee used to cycle for miles uphill to visit his wife’s house. They eventually got married in a modern day Romeo-and-Juliet-esque secret wedding in 1947 while studying together at Cambridge, fittingly, in Stratford-upon-Avon. Upon graduating from Cambridge, Mr Lee came back to Singapore with his wife and the rest, as they say, is history. The younger generation is perhaps not able to appreciate Singapore’s transformation the way our parents and grandparents do – I think I speak for most of my generation when I say that we look at Mr Lee with a sort of detached reverence in conjunction with vague ideas of what Singapore was like pre-independence that came with Primary School social studies lessons and Secondary Two History. I will admit that my interest in Mr Lee was mostly piqued in the last few weeks, which saw me belatedly devouring books and articles about his life and legacy, and the same is true of many of my peers.

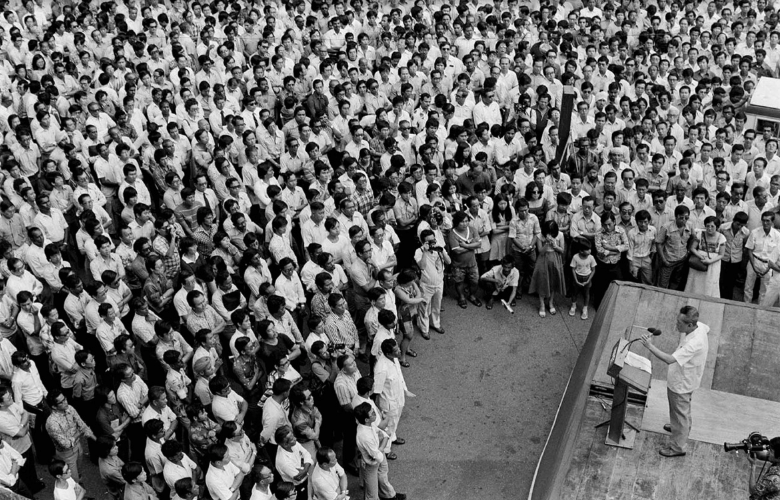

Mr Lee speaking at a People’s Action Party rally at Farrer Park in Singapore on Aug. 15, 1955. Agence France-Presse/ Getty Images/New Nation

As many from our grandparents’ generation shed tears at his passing and commemorate him with ever more ambitious projects (Mr Anderson Teo, for one, is currently building a model of Mr Lee’s Oxley house without a blueprint), our generation mostly mourns with posts on social media that are sincere but nevertheless reveal our lack of depth in appreciating and understanding the man. How can a generation that has grown up in relative airconditioned comfort (literally: air-conditioning is the single biggest factor in our energy use) understand just how far Mr Lee and his team have brought us?

It’s easy to forget just how much we’ve progressed in the last 50 years, yet it is also glaringly obvious when we think about it – rather than worry about where our next meal will come from, most of us worry about our grades and which university to go to – worries that our parents and grandparents never had the privilege to have. Things have gotten easier for us in Singapore, and it is up to our generation and others after us to further this legacy. It hit me today while scrolling through photos of the public paying tribute to Mr Lee that there is a generation growing up today with no first-hand knowledge of the giant at all. The photo of a two-year old boy clutching flowers and his mother’s hand reminds us that we teenagers have at least experienced Mr Lee’s charisma and determination first-hand despite not being fully able to appreciate the challenges that he had to overcome. Richard Nixon famously said of Mr Lee Kuan Yew that had he lived in another time and place, he may have attained the world status of a ‘Churchill, Disraeli, or Gladstone’.

Perhaps, perhaps not. What was evident even on the day of his passing is that Mr Lee Kuan Yew is Singapore’s George Washington – a founding father figure likely to be deified further as time goes on and generations spring up who have never personally known or experienced the gravity this man speaks with.

On the night of his death, I watch as my seven year old sister clamours for my father’s attention as we sit in front of the TV watching tribute after tribute to the great man, even as I, only ten years older and hardly more seasoned, follow the news with a heavy heart. Her idea of Mr Lee, and those of the children today, will come from the grainy black and white photos and the stories their grandparents tell — these stories too, may eventually fade away.

Mr Lee and Mdm Kwa Geok Choo returned to RI in 1994. They visited the Raffles Archives & Museum, then known as the Heritage Centre.

Mr Lee was certainly a controversial figure. Even in politics, a field famously full of people beating about the bush, he refused to mince his words. From ‘We decide what is right, never mind what the people think’ to ‘Everyone knows that in my bag I have a hatchet, and a very sharp one’, the internet is awash with quotes from him that come across as autocratic and almost certainly would not be welcome from any politician today. Immediately after his passing, bloggers and netizens were slammed for openly criticising his policies – most famously Amos Yee, but a whole host of other more moderate online voices, such as Jeraldine Phneah, who was forced to take down her posts after the uproar.

Some of this stems from the traditional Confucian respect for the deceased, but a lot of it seems to come from the unwillingness of Singaporeans to criticise those in authority, particularly our beloved leader. Looking back a few months later, it seems foolish to me that the culture in Singapore is such that we are unwilling to criticise our leaders. Though it preserves the image of the Mr Lee that has done a lot for Singapore, what good does it do if we remember only the good and ignore the bad entirely?

It is difficult to say if his authoritarian policies were the only route for Singapore’s development, or if we should instead have pursued a slower but more friendly path towards economic success. Yet does deification of this man really achieve any purpose?

Margaret Thatcher’s death sparked off many discussions, some more polite than others, about the soundness of her policies, as did Che Guevara’s death in 1967. We in Singapore should similarly allow, if not openly encourage, such a level of public discourse to fully understand the implications of his complex legacy. Coming from a position of relative privilege today, we can afford to look back and come to our own conclusions (with the benefit of hindsight), even as we laud the man for what he has done.

Mr Lee speaking to a packed lunchtime rally crowd at Fullerton Square in Singapore on Dec 20 1976 Agence France-Presse/ Getty Images/New Nation

Mr Lee will be remembered by generations of Singaporeans, and it falls to us to commemorate Singapore’s great man for who he is, not just the larger than life statesman with a self- declared ruthless streak but also the tender man who read his wife poems at her bedside nightly in her last days. As Singapore moves toward a less authoritarian direction with his passing, his creation of a ‘nanny state’ may either one day be seen as exactly what we needed in the first post- independence days, or strike future Singaporeans as overly harsh. Whatever it is, his policies and impact on our society will be remembered.

His achievements and astuteness will be extolled long beyond his passing, but what of the man who pragmatically proclaimed in 1969 that ‘poetry is a luxury we cannot afford’, yet toward the end asked that his ashes be mixed with that of his wife for ‘reasons for sentimentality’?

Even in his lifetime, we already saw Mr Lee as being larger than life. This will only intensify as we pass down the stories of his successes but not those of his controversies or his personable side — which, to me at least, is a shame. We will undoubtedly remember the great statesman and nation-builder, but we should also try to remember, as Mr Lee’s daughter Lee Wei Ling put it, the man who is ‘mortal… just psychologically stronger than most people’. His legacy is not just the rows upon rows of HDB flats and MRT lines, but also a much-needed reminder to all of us today that success does not mean giving up family or genuine human connection, that even the best of us may not always be right.