When it comes to revisiting memories, alumni of CHIJ and St Joseph’s Institution are, perhaps, fortunate in one respect; the restored shells of their alma maters live on as CHIJMES and the Singapore Art Museum. Although some of RI’s old boys and girls visit the former site of their alma mater often enough, the original Raffles Institution campus bordered by Stamford Road, Beach Road, Bras Basah Road and North Bridge Road is there no longer; in its place stands a bustling high-rise complex that has inherited part of its name. On Queen Street, where the Raffles Girls’ School building once regally stood, a memorial gate remains as a portal to another institution of learning—the Singapore Management University’s School of Business.

Singapore sometimes feels like a nation with little room for sentiment when it comes to old places, with citizens lamenting the disappearance of landmarks like the old National Library, National Theatre, Cathay Building, and the Marco Polo Hotel. Meanwhile, others accept, perhaps bitterly, that due to space constraint our homeland has become one with an ever-changing face. Even back in 1967, as the Central Business District grew and urban renewal gained momentum, the old boys of RI were emotional when President Yusof Ishak announced at the Old Rafflesians’ Association (ORA) dinner that their alma mater was destined to move. The Straits Times reported that they regretted that their old school had to be demolished; the Malay Mail lamented that an old landmark was to disappear.

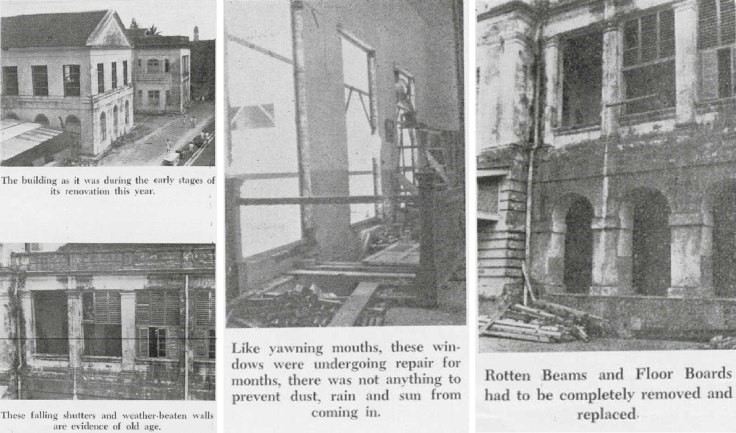

Yet, it was an indisputable fact that the Bras Basah campus was literally falling apart. In November 1967 The Straits Times published an article titled ‘RI Building declared unsafe by Public Works Department’, and Principal Philip Liau noted in the 1967 edition of The Rafflesianthat it is a ‘continual wonder that our dilapidated and obsolete science laboratories produce the best science results in Singapore’. Besides frantically shifting buckets across the classroom floor to collect dripping water whenever it rained, the boys also lived in constant terror of ‘windows hanging precariously from their hinges ready to fall’, to quote Mr Ung Bee Kok’s words in Under the Banyan Tree, a book written by alumni who studied in RI from 1961 to 1964.

Cartoon from the 1962 issue of The Rafflesian

‘Let me put everything into context for those of you who may have forgotten,’ he wrote. ‘The British reluctantly granted us self-government in 1959, but they controlled the purse strings so our own government was poor and there was no money and time to build enough schools for all the “baby boomer” students (those born after WWII) that were filling up our schools. Every school, especially the famous ones, was jam-packed with more students than they were designed for.’

‘Like master carpenters deliberately highlighting a flawed piece of wood to turn a weakness into an attraction, I’m sure we got our school colours from our buildings: its ancient whitewash, the black grime and the green of the fungi,’ joked his batch mate Mr Wan Meng Cheng in the same publication.

Photographs of the campus from the 1962 issue of The Rafflesian

A New Hope

Hence, the old boys’ feelings changed when they heard about the new site. Principal Philip Liau had managed to obtain a larger land area than was originally allocated. The new school was to boast facilities like a gymnasium, tennis courts, society rooms, lecture rooms, an audio-visual theatrette, a sports complex with a swimming pool and an 8-lane running track, and a Seiko Tower clock donated by Thong Sia Co. that eventually became the new campus’ most recognisable feature. On 5 June 1972, 149 years after Sir Stamford Raffles laid down the foundation stone in Bras Basah, RI completed its move to the new building.

Mr Liau was a man with a sense of history. He had spent 12 years as a teacher in RI, beginning in 1949, and returned to RI as Principal in 1966 after a brief stint in the MOE. In the 1967 issue of The Rafflesian he expressed his hope that ‘we shall leave behind the old buildings to be maintained as one of old Singapore’s few surviving landmarks,’ but it was not to be. A few years later, at RI’s final Founders’ Day in Bras Basah, he lamented how the old campus was to be demolished.

‘We could say that there is a history in every brick, a familiarity with every nook and corner and a benevolent air all over the place. Our regret must be one that what we have known and loved for so long will soon be committed to the misty pages of history leaving behind only a memory. To old boys who have spent most of their waking hours engaged in the many extra-curricular activities on the premises, the loss will be irreplaceable.’

The Bras Basah campus being demolished

Mr Liau’s determination to preserve memories of Bras Basah led him to purchase 15,000 bricks of the old school building from the demolition contractor for 5 cents each (the contractor, touched by this move, donated another 2,000 bricks). To further cement the campus in the annals of history, Mr Liau negotiated with Federal Chemicals for the presentation of a 1:100 scale model of the old building, which was installed atop a base constructed of the Bras Basah bricks on RI’s 150th Founder’s Day.

Introducing Mr Teo

Mr Anderson Teo and the Bras Basah model

Today, the model of RI’s Bras Basah campus takes pride of place near the entrance of the Raffles Archives & Museum. Prior to that, the model had sat on the second floor of the Yusof Ishak block, just above the porch where the bust of Stamford Raffles is located. Despite the prime location, not many had given it a second glance; it had seemed rather unremarkable under its grimy and heavy Perspex home, which took a few construction workers (who were then working on the renovation of the Museum), two RI students and a couple of teachers to remove. However it is, in Mr Anderson Teo’s opinion, one of the most detailed heritage models he has ever seen. And he would have seen many of them; after all, he has also worked on a model of CHIJMES, which boasts an intricate roof made of tiles in three different tones of red.

Mr Anderson Teo is a modellist. He had spent his childhood days in the 1950s living at the corner of Hill Street and Loke Yew Street, where he drew and sketched a lot of buildings in his free time.

‘I used to walk around the neighbourhood around Capitol Theatre, the old second hand bookstores at Bras Basah and RI. I was fortunate that I did not grow up at Hock Lam Street where all the gangsters were staying,’ he said. In September 1964, Mr Teo, then a 13-year-old student studying at Victoria School, made the first model of the Singapore Chinese Chamber of Commerce on Hill Street. Together with his mother he met Mr Lee Kuan Yew, who was invited to the building’s opening ceremony, and the then-Prime Minister was very impressed by the model. Mr Teo and his work were also featured in the Sin Chew Jit Poh and Nanyang Siang Pau(both predecessors of Lianhe Zaobao). Sadly, in a cruel twist of fate, Mr Teo’s mother passed away two months after the opening of the Chamber of Commerce.

Later in the 1960s, Mr Teo would go on to construct other models, such as the ‘National Showroom’ at the present Capitol Building (U/C). These were made of plywood. Incidentally, according to Mr Teo’s mother, his great-great-grandfather was a building contractor and carpenter who built the National Museum and the rows of terrace buildings at Teo Hong Road.

‘Life was very extremely difficult then, so I treasure what we have today after all those traumatic years of nation building,’ shared Mr Teo. ‘We have to give credit to our pioneer Cabinet Ministers, like the late Mr Rajaratnam, Mr Toh Chin Chye, Dr Goh Keng Swee, former President Yusof Ishak and of course, our amazing Mr Lee Kuan Yew, who dedicated his life to building Singapore from a poverty-stricken nation to a developed one.’

Sprucing up the Model

Mr Teo was brought on board by the Raffles Archives & Museum to, quite literally, spruce the Bras Basah model up. When I first met him, Mr Teo opened his bag and produced many miniature coconut palms that he had painstakingly cut and assembled from wood and paper. In the days before land reclamation, Stamford canal was an open drain and Beach Road really was near the beach; in fact, locals once called Bras Basah Road ‘hai-ki ang-neo tua-oh pi’, Hokkien for ‘beside the seaside English big school’. The ample supply of water supported the thriving coconut colony that bordered RI’s school field.

Mr Teo had also fashioned little wide-canopied trees from sponge; the existing ones in the model, now fluffy and dull, were made of steel wool. He brought out figurines of people, cars, and a host of basic tools he uses when working on architectural models. Most of these would be familiar to people who dabble in crafts—brushes for sweeping dust away, clear UHU glue for affixing objects, pencils, penknives—but the set of imperial triangular scales, which he has been using since the 1970s, are of special sentimental value to him.

Mr Teo’s tools

The scales are important, Mr Teo explained. Viewers can tell right away when proportions are off, so one has to be careful with measurements. It is also important to ensure that all the props are historically accurate. Mr Teo had to search for car models with designs from the 1950s and 1960s, which are hard to make and obtain.

‘Afterwards, I’ll spray-paint the cars grey to tone down them down so the buildings stand out. I also do this for condominium models, and commercial models like the one of Clarke Quay,’ he said.

Modern-day condominium models are computer-cut, so making a model by hand in the 1970s must have been quite a painstaking task in comparison. All parts of the Bras Basah model were hand-painted, and groove lines can be observed on the roof, which was stuck on piece by piece and given a semi-gloss finish to make it easier to clean. The school field was made from very fine sawdust in two tones; first in green, followed by an overlay in brown. The field also boasts natural-looking watermarks that were made to resemble ponds. The main and annex tuckshops both housed miniature benches, so Mr Teo used tweezers to gingerly populate them with miniature figurines without damaging the existing structures. He also added more cars and trees of variousspecies, touched up the landscape, and retyped all the labels on acrylic.

Mr Teo populated the canteen with tiny figurines

Architectural Features of the Bras Basah campus

Mr Teo pointed out several interesting architectural features of the old campus that can be observed through the model:

1. Many modern buildings in Singapore are built on an axis parallel to the road, but the spine of the main block that borders Beach Road was actually slightly tilted (on purpose). The architects had also created a stepped rhythm with the blocks; this can be observed from a bird’s eye view of the model.

2. The model is so detailed that it includes rain water pipes! Rainwater slides down and collects in the gutters that run along the sides of the roofs, and the pipes carry the water down from the gutters to the open drain below.

Mr Anderson Teo points out the rain water pipes in the Bras Basah model

3. Some blocks were built on stilts to prevent floodwaters from damaging the upper levels of the building. On hot days, the ventilation openings between the stilts also lowered the temperature in the building—the cooler air in the openings flowed through the rooms via the timber floorboards, and the high ceilings of the rooms further promoted air circulation. There was no need for air-conditioning in those days!

The timber floorboards were mouldy and creaked a lot. Most horrifyingly, Mr Siu Kang Fook (RI, 1968), an alumnus, revealed that the floorboards sometimes gave way.

Ventilation openings

According to Mr Siu, the model contains several inaccuracies that Mr Teo had to correct. The positions of the iconic Banyan Tree (which should have been near the Tuckshop) and the rugby poles were previously inaccurate, and the model also neglected a covered walkway between the Tuckshop and the toilet. Mr Siu, who is currently helping out at the Raffles Archives & Museum, also described how a two-storey staff block that used to stand next to the block that housed the Principal’s Office was demolished due to termite infestation years before the model was made.

The World Behind the Walls

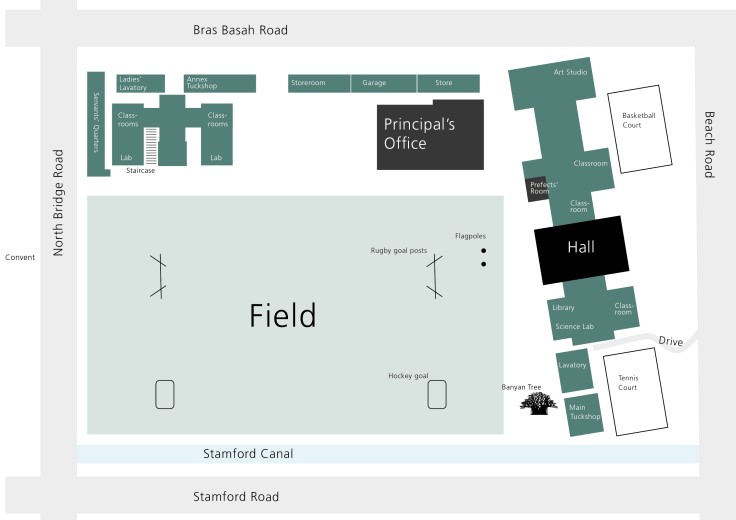

As the interior of the buildings cannot be captured in a model, Mr Siu drew a rudimentary map and labelled the blocks: The Main Tuckshop, the Annex Tuckshop, the Hullett Memorial Library, the School Hall, Principal’s Office, Prefects’ Room, laboratories, Annex E (which once housed RGS), classrooms, and storerooms. In the 1950s, the cadets’ armoury—where rifles and sports equipment were kept under lock and key—housed the Bras Basah Post Office, which moved when RI expanded.

A rough map of the Bras Basah campus

The Principal and school servants used to live and work in the school compound. While the servants’ quarters were located at a corner of the campus, the Principal’s room was located right above his office. All the Principals preceding Mr Ambiavagar were ‘Britons who had reached the zenith of their careers and had nowhere to climb higher but to retire in a few short years’, as Mr Philip Liau explains in the 1977 issue of the Rafflesian. Once every two years they would undertake a three-week-long odyssey home, spend two weeks with their families and friends, then spend yet another three gruelling seaborne weeks journeying back to Singapore. Sometimes, the Principals worked on a rotating basis with their peers from Victoria Institution in Kuala Lumpur. For example, Mr Bishop, who became Headmaster of RI in 1921, was previously Headmaster of Victoria Institution. When he came to Singapore he brought along one of his scout teachers from VI, Mr K Sabapathy, who restarted Scouting in RI in 1922 by forming what was to become the 02 Raffles Scout Group.

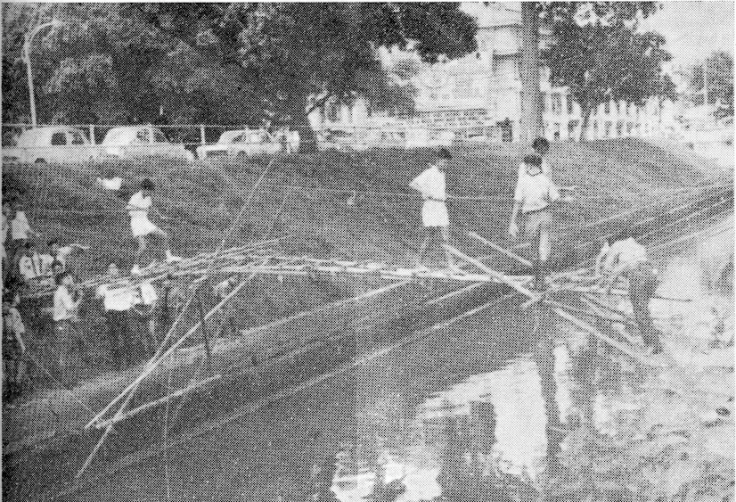

Speaking of the Scouts, it is a pity that one of their contributions to the school community was not captured in the model: the boys had put their nifty pioneering skills to the test and built the proverbial bridge over the troubled (and putrid) waters of the Stamford Canal facing St Andrew’s Cathedral. ‘That one was just for fun only lah!’ laughed Mr Siu when asked about the bridge. Nevertheless, the RI boys found it handy, using it as a shortcut to get to Capitol Cinema, racing across Stamford Road before any of the school staff could catch them. Sometimes, the boys would even make a quick detour to the cinema to purchase movie tickets when they were supposed to make their way from their classroom to the science lab.

Bridge over troubled (and putrid) waters

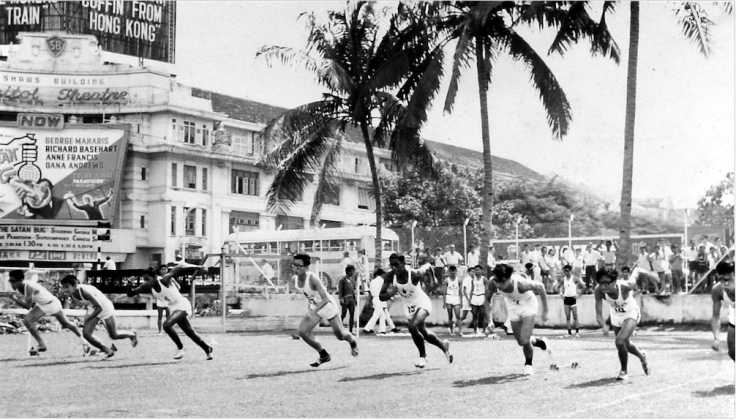

View of the Capitol Theatre from RI in 1965

The Bras Basah campus had borne witness to so much of Singapore’s history, through its development from a fishing village to a bustling port, through tumultuous years of nation building. During the Second World War, the British had used it as a military hospital for injured troops, and when the Japanese took over they used it a military camp, burning the furniture for firewood and burying all the typewriters as they could only produce English letters. They even ploughed the school field and used it to farm tapioca and other vegetables. After the war, the Bras Basah campus lived through days of racial riots, the Konfrontasi, merger with Malaysia and the birth of a new country. Its demolition marked the end of an era and the beginning of another.

‘History must make way for Prosperity’

Raffles City was officially opened in 1986 by an old boy of RI, then-Deputy Prime Minister and Defence Minister Mr Goh Chok Tong. ‘This piece of land on which Raffles City stands has a special meaning for me and many Singaporeans,’ he said at its official opening on 3 October 1986. ‘For it was here that Raffles Institution proudly stood, for more than a century. And it was here that thousands of us spent many joyous years.

‘But proud as Rafflesians were of their old school buildings, they recognised that history must make way for prosperity. It was thus with more than a casual interest that they looked forward as to who would take the place of Raffles.

‘This evening it is my pleasure to officiate the opening of Raffles City. It is indeed auspicious that the owners have decided to call this complex of modern towering buildings “Raffles City”. For the name “Raffles” carries a big reputation of excellence. And Raffles City will have to live up to that reputation.’

Raffles City was the largest development project in Singapore at that time. It boasted what was then the world’s tallest hotel (Swissôtel the Stamford), and it was to link the CBD with the expanding tourist, shopping and entertainment belt that stretches from Orchard Road to Marina Bay.

The architect appointed for the job was I M Pei, who had designed the controversial glass-and-steel pyramid for the Louvre in Paris and the Bank of China Tower in Hong Kong. Mr Teo pointed out that much like the Louvre pyramid and the Bank of China Tower, the shape of the Raffles City complex (when seen from the top) consists of timeless geometric shapes: circles, triangles, squares. Moreover, from a bird’s eye view, one can see that the shape of the complex originally comprised four interlocking small letter ‘r’s prior to the addition of new extensions. Raffles City’s modern design is a stark contrast from its colonial neighbours: Raffles Hotel, CHIJMES, Capitol Building and the Singapore Art Museum.

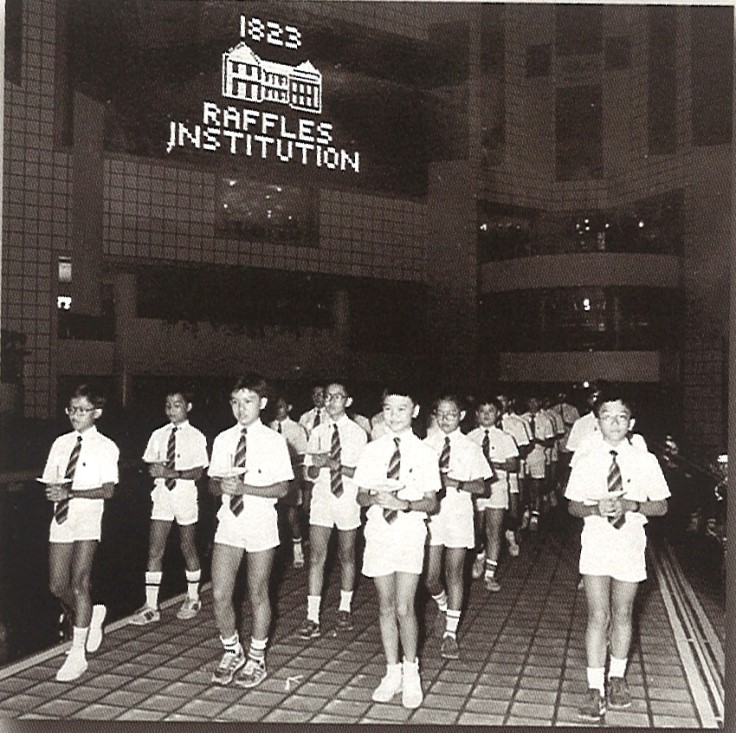

At the opening of Raffles City, 40 candle-bearing RI students walked across the atrium’s glass bridge. As the boys left, the bridge burst into light and sound.

The Bras Basah campus may be gone, but it lives on in a 1:100 scale model in the Raffles Archives & Museum and in the hearts of the old boys who spent significant years of their lives in its hallowed halls.

‘For four years, we did not live on fresh air and sunshine alone,’ wrote Mr Wong Wee Nam in Under the Banyan Tree. ‘We lived on the stench from the Stamford Canal and the aroma from the Satay Club; and survived on food from the tuckshops. We also managed to live through a turbulent age of emotional, developmental and political turmoil unscathed. Today if we had been turned from jagged rocks into sparkling gems, we owe it to the school, the teachers, our peers and the events of our time. Looking back, Hope (from Hope of a Better Age) was both a verb and a noun.

‘Soon after we left RI, the school was demolished. Physical structures of the school may have been buried beneath Raffles City, but it could not erase the memories of our times in RI. Time and age, however, may have diminished and distorted our recollections but there are some events that just do not fade away. These vivid memories and the blurred recollections are the ties that are binding us together as Rafflesians today.’