Theophilus Kwek

This article is part of the RI at 200: History Series.

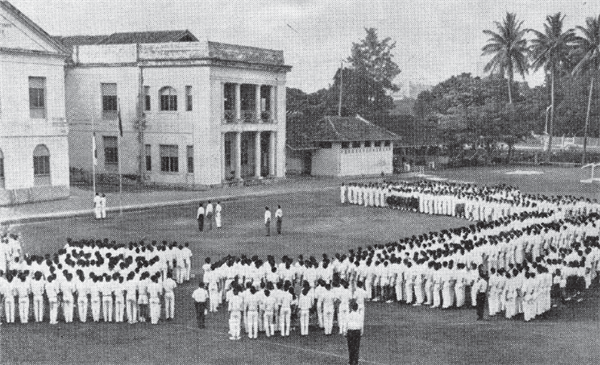

First Flag Raising Ceremony in RI

30 August 1966

Imagine, with me, the scene of boys and girls milling about the school field at Bras Basah on the morning of 30th August, 1966 – some gathering in the shade of the old banyan by the tuckshop, others in the portico of the neo-Palladian library, one of many such buildings dotting the streetscapes of late colonial Southeast Asia. A salt breeze hovers over the campus, and the sun has just begun to climb the coconut trees lining Stamford Canal on the field’s southern fringe, striking the distinctive façade of Capitol Cinema that still looms large in their memories, many years later. 1

Then, a bell rings. The students shuffle into rank and file, craning their necks as the national flag is raised, haltingly, for the first time. They raise their right hands2 for the pledge: “We, the citizens of Singapore…”. A few stumble over the words, which have been painstakingly drafted in an earlier version by Philip Liau (recently returned to the school as Principal, after a stint at the Ministry of Education), and reworked by Ong Pang Boon and S. Rajaratnam less than a month before. But all is forgiven: if these phrases are unfamiliar, it is because their novelty has not yet faded into ritual. With all the power of their newness, a new nation is spoken into being.

“We have come to accept the flag-raising, anthem-singing and oath-taking as part of our curriculum”, wrote the editors of The Rafflesian (Vol 40 No. 1, 1966) just months later. “But we realise the need to delve beyond the letter of the oath and arrive at a humane, realistic and practical concept of national consciousness, if the pledge is not to degenerate to the level of the normal and the routine”.

Mr John Young

Principal of RI, 1954-1957

That this soul-searching should come so soon3 after the ceremony was introduced is hardly surprising if we consider the weight of expectations on the era’s Rafflesians, who, in the waning years of the British Empire, found themselves at the forefront of a policy to shape the elites of its erstwhile dominions into citizens of self-governing nations. A decade earlier, following Singapore’s first elections under the Rendel Constitution, Principal John Young had already observed that his charges would “have to carry responsibilities that their fathers never had to”, and that it was the school’s duty to prepare them for “the onerous responsibility of citizenship” (The Rafflesian Vol 25 No. 1, 1955).

But what did it mean to be a citizen of a country that had only just come into being? Rafflesians on the field that morning had no ready-made answers to the many questions arising from the end of Empire or the shock of Separation. School administrators naturally provided some direction: Principal E.W. Jesudason, for one, introduced “the singing of various community songs of different races” to foster a sense of national unity.4 Yet it is in the pages of The Rafflesian that we see, first-hand, how the students themselves resolved to live out the promise of that post-colonial moment.

“True national consciousness […] must be actualised by a bond of sympathy between individual Rafflesians, between individual Singaporeans, who understand one another as human beings with common needs”. The editorial committee of 1966, led by Peter Chan (later Chief Executive of the Housing and Development Board), urged their peers to ground a new sense of belonging not in how they were seen by many – as the education system’s ‘crème de la crème’ – but in an awareness of shared needs and vulnerabilities. Rather than “parochialism or ‘mark-grubbing’”, they wrote, this common humanity should provide a foundation for solidarity. A nation, after all, was not merely a “vague idealisation”, but formed of “men, women and children who are real individuals”.

N. Logaraj, a Pre-U 2 student (also winner of the Jesudason Trophy for public speaking that year), took up the question of what this solidarity would entail in his essay “The Ideals of the Commonwealth”, reprinted in the magazine. Reflecting that “we live in an era of strife and turbulence […] unrivalled in the history of the world”, he believed it would take nothing less than a “profound emphasis on individual dignity and economic welfare […] to alleviate these deplorable moral and material conditions” for all. In turn, a pursuit of dignity and welfare would require Singapore, along with other Commonwealth nations, to commit itself to liberal parliamentary democracy, individual freedom, the rule of law, and racial equality, in recognition that “man by virtue of his inherent dignity is entitled to the fullest respect and well-being that the State can provide him with”.

There was an aspect of universalism to these ideals. As Logaraj went on to argue, no country should deny their people “the basic, fundamental rights […] essential for a full and decent existence”. It was “preposterous”, he thought, that any regime would claim that “more progress can be achieved through [the] denial of these privileges”. Clearly, the Rafflesians of the day envisioned a solidarity that went beyond national boundaries. Another essay by Pre-U 2 student Natarajan Varaprasad (“Universal Diversity vs World Unity”) contended that nations should “work together so that all of them might live a better life”. Such global cooperation, too, would be founded on a sense of shared precarity, in the realisation that “no country in the world can be said to be completely self-sustaining”.

Prof Toh Chin Chye inspecting the cadets at the 1966 Founder’s Day parade

The hopes that these Rafflesians espoused were at least partly inspired by the rhetoric of the hour: at Founder’s Day in 1966, Deputy Prime Minister Toh Chin Chye had reminded them to eschew individualism and cherish the “solidarity [...] which is so important for sustaining our independence”. But they also arose organically from a rich calendar of student activities, which nurtured and gave expression to the students’ beliefs. That year, the Historical Society invited Dr Sharom Ahmad, a keen advocate of social development and lecturer at the University of Singapore, to lead a discussion on “the role of developing nations in the United Nations”, while ethnographer Dr Ivan Polunin (who documented life in the Malay Archipelago for the BBC) was asked to share his research among the orang laut. Not to be outdone, the Economic Society organised visits to factories and shipyards in Jurong, and also to the recently-completed satellite town of Queenstown: a bright symbol of the “individual dignity and economic welfare” that Logaraj yearned for.

These records give us some insight to the hopes and ideals of Rafflesians in that first year of Singapore’s independence; teenagers who, in the words of Head Prefect Lam Pin Kwee,5 were proud to “think more of the community than ourselves”. Uncertain though the times may have been, they and many others in their generation found ways to put a newly-written pledge into practice – and in so doing, fashioned themselves into “better citizens of tomorrow”.

Theophilus read history and politics at Oxford University, and has written widely on citizenship and migration issues. He is also a poet, and has been shortlisted twice for the Singapore Literature Prize.

_____

1 Recollection of Er Kwong Wah, Pre-U 2, 1965.

2 The practice of reciting the pledge with a clenched right fist over the heart was only introduced in 1988. See Zhi Wei and Kartini Saparudin (2004), “National Pledge”. Singapore Infopedia, National Library Board. Available online at: https://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/infopedia/articles/SIP_84_2004-12-13.html.

3 Two decades later, these questions are reprised in a series of forum debates, prompting the Ministry of Communications and Information to commission ‘We Are Singapore’ (which incorporates the pledge in its 8-minute track) as the National Day song for 1987.

4 Recollection of Choo Chiau Beng, then in Pre-U, who later served as Chair of the RI Board of Governors.

5 A keen footballer, Lam later studied medicine at the University of Singapore. His Founder’s Day speech is printed in The Rafflesian.