by Catherine Zou (17A01B), Bay Jia Wei (17S06R) and Serafina Siow (17A13A)

The term has come up with such regularity for the best part part of our school lives,

but what does it really mean beyond a theoretical quality that we are urged to have?

How do we engage this familiar, yet foreign, term in our daily lives?

When asked about their definitions of empathy, Rafflesians’ responses ranged

wildly from a quality that may be unattainable for some mortal beings, to a #lifegoal

to strive towards. Across varied responses, the common denominator was ‘understanding’. Some thought it to be something that steers away from “self-gratification” and that it is to ‘[make] a conscious effort to understand others so that support can be as sincere and genuine as possible.’

We do witness many kind acts in the Rafflesian community. A friend could

be sitting down to guide someone through a mathematics paper even

though he has his own revision to do, or a classmate could be asking another

how they are feeling.

Raised on a diet of fairy tales and Hollywood movies, we have been brought up to think that good deeds are the result of good character.

But what we intuitively sense is that something more complex is taking place instead. In reality, however, actions that are objectively ‘good’ or ‘kind’ may be driven by reasons other than overpowering compassion. Kindness, it would seem, is the consequence of several stimuli. While ‘empathy’ is a trendy byword for these reasons, we hypothesise that it works alongside other factors such as societal pressure, a sense of obligation, or simply nonchalance.

As such, we decided to conduct a social experiment to investigate the reasons behind our kind deeds.

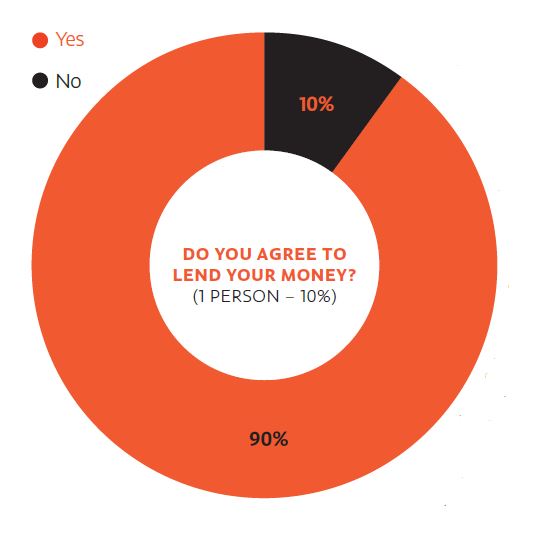

The 10 participants were then asked to explain their actions in our bid to explore the thought processes and considerations that took place before the decision ‘to lend, or not to lend' was made.

First, the shock. Then, a stare of incredulity at an empty wallet. A few seconds of fumbling and apologetic murmurs follow, before finally turning around – ‘Sorry, could you lend me a dollar?’

For the 9 out of 10 unsuspecting participants in our experiment, it was this perceived desperation and helplessness of our actors that prompted them to contribute a portion of their wallets. The sense that their schoolmate genuinely needed help was an establishing factor of their final decision to lend the money. This is the small intermediate stage that provokes an empathetic emotion.

For the 9 students who agreed to lend their money, their sense of empathy was an important emotion that moved them to consider extending a helping hand, with 6 of them naming it as a key reason for lending the money.

This factor is centred around predominantly around concern for the person in need, which means that it can be seen as a more noble or moral reason.

Responses such as ‘I guess if I were in the same situation I’d want people to lend me money as well’ and ‘I felt that it would be quite difficult for you to last the day without food’ placed themselves in the perspective of the asker and empathised with their predicament.

Interestingly, the contrasting example of the student who had declined to help showed that they did not relate personally to the situation: ‘I’d lend it to a young child, but you’re old and can manage yourself’. These instances indicate that the emotional pathos drives us to consider whether or not to agree to help out someone in need.

Almost all participants revealed that they had agreed to lend the money, for it was ‘within [their] capability’. Because they were more than able to offer the extra dollar or two, it did

not cause them any significant loss. When asked if they would consider lending a greater amount of money, all of them either declined or would only consider extending a helping hand, if they were reassured that their money would eventually be returned.

This implicit level of trust was also one of the key considerations for a few participants, who only agreed to lend their money after the actors fervently promised to return the

amount. Similarly, one of the participants declined to offer her assistance for this very reason. As she later very frankly explained to one of our journalists, she ‘did not trust that the money would be returned’. However, another participant shared that her main motivation in extending a helping hand was because the actor was ‘really in need of it’ and that whether or not he chose to return it was not a consideration that she had.

When asked if they would lend their money to a member of the public outside of school, participants’ had diverging responses. On one side, a third of the participants said that they would if it was ‘within [their] means’, once again reflecting their willingness to help if they would not be disadvantaged as a result. Another third would choose not to as they thought it would be highly unlikely for their money to be returned.

The last camp was undecided, citing ‘how trustworthy the person appears’ – whether or not they seemed to really need help or that they would return the money – to be their deciding factor. A plausible explanation for the responses would be that the school community has a more trustworthy image than the public sphere, which may seem more foreign and unpredictable.

A slightly subsidiary factor is the momentum of the exchange, given that it is easier to agree to help than to decline and risk a negative reaction or experience. If empathy and

pragmatism are seen as the tension between self-interest and people-centredness, this factor is the outerlying area that just ‘goes with the flow’.

One student raised this idea by shuddering when considering the consequences that may unfold from a rejection: ‘It’d be super awkward for […] both of them in the situation’. Comparatively, agreeing to help often entails nothing more than a quick nod, a smile, a note — the dynamics involved are simple, predictable, and familiar. Especially given the small amount of money involved and the even more marginal risk of not getting it back, one tends to find it easier to lend their help.

This is typified with the response ‘since you need money and it’s well within my means, I might as well as be helpful and lend you that money’. This point is valid – what if you see the person around in RI, and are remembered for refusing to help them out? Sure, you could have made up a convincing excuse, but the guilt is there.

Not quite empathy (the decision is not founded upon great compassion for the person) and not quite pragmatism (the decision doesn’t hinge on the money and whether it would be returned), this factor nonetheless gives considerable impetus to a positive response. After all, both social pressures and the momentum of the conversation generally make it appear easier to accede to the request rather than to deny it.

While the decision to loan money hinges on empathy or pragmatism or not quite either, the result of the decision being ‘yes’ matches up with our observations of kind deeds being done in the Rafflesian community. Be it an outpouring of compassion, societal pressures, or generosity with marginal loss, we all have our own combination of motivations for acting kindly, be it going out of our way to volunteer for good causes (as we explore in the article Service and Kindness) or merely to lend a helping hand when requested.